I am supporting value chain practitioners in various programmes where I am coaching, teaching, supporting, pushing and pulling experts. This is one of the perks of my job as I get to look over the shoulders of practitioners working all around the world on commodity, agricultural, manufacturing and service value chains.

While marking some assignments for a course I am tutoring for the ILO I realized that many practitioners are trapped in a particular chain, just like the actors that they are trying to empower. With trapped, I mean that they are working with the actors and the chain for the benefit of the chain. They completely miss the broader impact of their work. (I know that this is often more the fault of the people who design programmes, more about this elsewhere in my blogs).

Let me explain.

For me a value chain is something we construct so that we can understand a part of a sub-system. If you are diagnosing a tomato value chain then it is true that you are getting a deeper understanding of the tomato system. But you are also gaining an insight into an agricultural system, a regional system of stakeholders and communities, but also an insight into the national or maybe even global economy. While some value chains exists in a very formal way, with contracts linking the different actors, most value chains can rather be described as temporary social phenomena. Temporary because they tend to change over time.

Back to my main argument. While it is true that value chains are known by their end products or markets, there is more to a value chain than just the conversion stages of a product/service. Value chains show us how an economic system works. It show us how responsive institutions and supporting organizations and indeed a whole society is towards economic activities of a certain kind. Value chains also tell us some fluffy yet important things about the society it is framed by. It tell us something about the social relations, the search costs (finding people to do business with), the social capital (how well we trust each other, how easily we collaborate), the enabling environment, and the returns on investment and effort in different parts of the system.

So if we find that tomato farmers are not very sophisticated, that they have poor market relations, that entry barriers are very low hence nobody has an incentive to invest, that suppliers are dishonest, that there are some new market niches developing but that nobody knows, that intermediaries have disproportionate power; I am not surprised at all. In fact, your findings are rather typical, even predictable in some sectors. What I am surprised by is if you treat this like it is a unique finding contained only to the tomato farming sector. The chance that these characteristics are contained only to those involved in the tomato chain is rather slim. This is the real risk of having a too narrow product focus.

Yes. Value chains are known by their end markets or products. But no, we are not locked into a product. We want to understand the system better so that we can support the emergence of institutions, market systems and interventions that make the whole system work better. Those issues that I outlined before in my tomato example can be verified in the sectors or crops around it. In my experience, many crops or business sectors sometimes have similar challenges. Therefore instead of trying to work at a low scale with some tomato farmers, you could possible be working with 10 crop types in a region, involving 1000s of farmers, and maybe a dozen supporting institutions. Few extension services for instance focus on one crop, they often handle a variety of crops, animals and markets. So you have to try and understand what each kind of economy activity (like farming with tomatoes) have in common with other business types or farms, and then what is unique. When you do this you often find that the actors in the chain have far more in common than the product or crop. They could all be equally unskilled, equally under-capitalised, equally vulnerable to market fluctuations, equally exposed to poor contract enforcement, or monopolies. This is how we get to real systemic interventions.

Yes. Value chains are known by their end markets or products. But no, we are not locked into a product. We want to understand the system better so that we can support the emergence of institutions, market systems and interventions that make the whole system work better. Those issues that I outlined before in my tomato example can be verified in the sectors or crops around it. In my experience, many crops or business sectors sometimes have similar challenges. Therefore instead of trying to work at a low scale with some tomato farmers, you could possible be working with 10 crop types in a region, involving 1000s of farmers, and maybe a dozen supporting institutions. Few extension services for instance focus on one crop, they often handle a variety of crops, animals and markets. So you have to try and understand what each kind of economy activity (like farming with tomatoes) have in common with other business types or farms, and then what is unique. When you do this you often find that the actors in the chain have far more in common than the product or crop. They could all be equally unskilled, equally under-capitalised, equally vulnerable to market fluctuations, equally exposed to poor contract enforcement, or monopolies. This is how we get to real systemic interventions.

But the idea should never be to promote some products. This is the job of business people and entrepreneurs, not development practitioners. No, development practitioners should try to understand and strengthen the system. We make the features of the system that is overlooked or not visible to stakeholders more apparent. I also dislike it when practitioners start with an hypothesis that profit is unfairly distributed, or many of the other typical biases that exists in this field. The simple truth is that investments in economies flows to where there are (visible) returns. If it becomes more profitable to invest in retail than in manufacturing or farming, then this tells us something about the system. It is an important finding in itself which then allows us to ask the next question “how to make farming more profitable for investors (farmers and the poor are also investors)?”.

Your value chain has more value in it than the value added at each stage of the chain. What is valuable is the insight you are gaining about how a part of the economy works. Don’t become a product promoter. Be a system builder.

July 17, 2012 at 10:43 am

I really appreciate the idea of using the VC approach for *understanding* the system. Yet I would like to understand better how you can use it to *change* the system(s). In fact -as a confessed value chain ignorant- I always thought the VC approach was a way a reducing complexity. Using your example: if you know before even starting the project that farming skills are dismal across the board, but you know you’re now going to be able to educate the farmers and extensionists on all topics, you focus on those aspects relevant to your VC so you can see some impact. That impact is going to be valuable because you tackle the daunting task of improving marketing (let’s assume it is deficient for all products) by at least improving marketing of tomato products. Etc. So yes, you should derive more general conclusions from your VC experience – but how do you put them into practice without getting lost?

LikeLike

July 17, 2012 at 12:50 pm

Dear Valérie,

Thank you for your comment and question. You always seems to be the first!

I agree a value chain is a way to reduce complexity, although the diagnosis might reveal quite a lot of technical data, and maybe it also reveals a complicated system. As development practitioners we typically get involved in the parts of the system where the performance is dismal, I work with very few practitioners that are working in the side of the system where the target groups of very innovative and dynamic (although they also have their own challenges).

My point was more that working in one VC could itself be a trap, in that many opportunities for interventions do not make economic sense when you work with smaller numbers of actors. However, if you treat your diagnosis as being representative of a larger system, AND you verify that other related or similiar chains are confronted by the same issues – then you might be able to propose interventions for a broader system.

As development practitioners we have to be able to ZOOM in at the appropriate time and focus on a single product chain or target group, but then we must also be able to ZOOM out to get a broader perspective. This is then by zooming in again where appropriate. We should not get caught at looking at a whole system just from one perspective. Our challenge is that we know that generic solutions offers dispersed or low impact, while too focused interventions might be too specific to influence the larger system even when it is surgical.

Best wishes,

Shawn

LikeLike

July 17, 2012 at 1:26 pm

Thanks Dr Shawn!

The key message I keep is “to propose interventions for a broader system” while going ahead with concrete improvements in the VC at hand. Meaning that any VC project should have 2 objectives: (1) to reach concrete impact on the selected VC; (2) to derive policy recommendations/intervention proposals from the analysis that are apt to improve other parts of the system.

Best fro mGermany,

Valérie

LikeLike

July 17, 2012 at 1:38 pm

Valérie, you have summarized it perfectly!

Perhaps I can add a third to your two messages, and that is to not only measure impact at the level of the specific chain, but also at the level of the system. Can we learn something from this specific chain that is useful or relevant for the larger system?

Best wishes from South Africa.

LikeLike

July 18, 2012 at 3:04 pm

Dear Shawn,

The discussion on the perspective of the value Chain is opportune for our Province Limpopo where despite being one of the largest tomato farming communities in the world we have Italian value chain tomatoes in our doorstep at half the price of the local manufacturer (R9,00 per 250 g can versus R10.00 for the Italian brand which is also fortified with herbs). I believe the local manufacturing “chain” is diaggregated and only interested in a single crop/commodity mindset and myopia. The Italian canned tomatoes competition does however present a tomato sector economic systems overview. I am sure that out tomato systems value chain and economic system can be one such good example on a globals cale and may also include other crops.

Greetings from Sunny Limpopo – The World Capital of Tomatoes!!!!!!!

Nepo Kekana

LikeLike

July 18, 2012 at 3:55 pm

Hi Shawn,

nice to read your blog, what me recalls the session on Value Chains we facilitated together at our Mesopartner Summer Academy in Berlin two weeks go. Thank you, again for this experience.

I like your expression that “a value chain is something we construct”, or in other words “a value chain is a mental construct” which we shouldn’t confuse with the real world.

Why do we need such kind of mental construct? Well, our aim is to improve the living conditions of people in developing countries which is quite ambitious and broad purpose. In this situation the VC approach helps us to reduce the scope and complexity to identify a specific way to understand (parts) of the whole system and find leverage points. BTW, we do the same, when we are promoting Local Economic Development, even as there is a real territory, it is only a mental construct.

Setting boarders is necessary to understand and intervene, but at the same time we have to be aware, that there is a broader reality with implication within our mentally constructed system.

In that sense, the definition of a VC by a product is a simplification of the real reality. My practical experience is, that it is very helpful to reconstruct a value chain from a specific product (against the flow of the productions process). At the same we have to be aware that even the reality of a VC is more complex. Once built your VC you may ask for alternatives, i.e. the production of other products, connecting links of the VC to other chains (“VC network”) or introduction of new technologies or even business models.

In our work it is a thin line, between to make a system workable and to oversimplify the real system which we like to influence in a positive way.

Kind regards,

Cheulrico

LikeLike

July 19, 2012 at 11:44 am

Thanks Shawn for this stimulating perspective – so ….a VC is part of a broader system and divorcing it from the system is basically for ease and manageability, but more than informing us about what is happening is the chain, it gives information and insight of the system

LikeLike

July 26, 2012 at 6:58 pm

Dear Shawn. Thank you very much for this post that nicely illustrates what it means to have a systemic perspective when working with a Value Chain Approach. The really valuable insight is that we cannot only have a bigger impact on our target chain when we take a systemic look but we can actually have a bigger overall impact by tackling constraints that are not limited to our chain but are a problem for the broader (e.g. agricultural) system.

I can illustrate that with a nice example from Bangladesh from the famous Katalyst project. Katalyst introduced what they call cross-sectoral interventions. For example, they are working in the ICT sector looking for solutions that can benefit their sectoral interventions. One such example that I was introduced to during a visit to Katalyst is the establishment of a hotline that farmers can call if they have any questions regarding their production. The hotline is fully implemented by the private sector, i.e. the second biggest mobile phone company in the country, which also uses it as a marketing instrument (the hotline is only accessible if you are a subscriber to that particular company). With that, Katalyst did not only have an impact on the agricultural sub-sectors they were targeting, but on the whole agricultural sector – since the hotline was a success, the thematic base was expanded to cover more topics. There were even talks of introducing similar hotlines for advice in health or legal issues.

Best,

Marcus

LikeLike

August 1, 2012 at 3:12 pm

Dear Shawn,

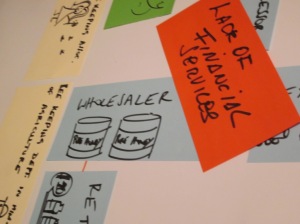

Very good points you make here! You can find a figure illustrating your concerns (being trapped in a particular chain and not recognising the impacts on the broader system) in Annex III. This is not based on our creative thinking but we took it from Bowig et al 2010. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/—emp_ent/—ifp_seed/documents/publication/wcms_170848.pdf

Best wishes,

Christian

LikeLike

August 4, 2012 at 9:05 am

Thanks for the post Shawn.

True enough that the value chain is an analytical tool. My experience is that you can use it to chart a system, and a sense of local intricacies. Turning that into action is something else.

My team and I are rounding up a research project for the ILO where we trialled a business model perspective to value chain analysis. We analyzed lead firm (agri) business models, and discussed the effect to value chain impact on labor from there.

The main things I learned from this approach is that the potential of the business model perspective lies in applying it to the chain actors with influence. You can use the value chain to determine who has influence. Consequently you are able to apply a process of business model innovation at that level to bring about system change. The business model perspective also hints at where the limits lie to the sphere of influence of value chain actors. Very important, as influence is often presumed to be larger than it actually is, and gives rise to misguided interventions.

I will be writing out my thoughts on the ILO research in the coming time on my blog. Stay tuned!

Bart

LikeLike

October 4, 2012 at 12:31 pm

[…] on my previous e-mail that even resulted in me having to speak at some events about there being more to value chains than just diagnosing a value chain. Thank you Paul for drawing me into your organisation to address your team about diagnosing value […]

LikeLike

December 18, 2012 at 9:14 pm

[…] those that are interested to know, my most popular post was about there being more value to value chains than adding value to products, followed by localization and building domestic manufacturing capacity and supporting business that […]

LikeLike